John Henry Chapter 5 - Susan Garlinghouse DVM

John is now 24 years old, and as far as I know the oldest horse to toe up to the line this year (the oldest ever was 26). It will be John’s last trip to Robie Park, and I sincerely thank every one for their kind interest in his journey looking to be the only gaited horse to finish Tevis six times.

The point of this Nordic saga isn’t about me, or even about John Henry, though he is truly a great horse that I’m told has encouraged many to give distance riding a try.

These stories are about all of us who meet our challenges with less than perfect bodies, a less than perfect life, and riding not necessarily the perfect endurance horse. We all have other distractions in life. We all have a story. We just need to tell them to teach and inspire others, learn from them and never, ever, ever give up.

Seventeen miles and three hours after leaving Foresthill, we came into the Francisco’s checkpoint at 85 miles. It was now 11:30 at night, still in the high eighties without a breeze, but we were feeling strong. John was eating voraciously, his hydration and metabolics were good and he sailed through the check with a pulse of 56 four minutes after coming in. I grabbed a flake of wet hay as we left on foot and handed him snatches of it for him to munch as we made our way towards the river crossing at 90 miles.

I had never crossed the river, certainly not at night, and wasn’t sure of what to expect. With his swimming background, I knew John would plunge right into the water like a stampeding hippo, and he did. He stopped chest deep to take a long drink while I scooped water onto his neck and shoulders, and then marched across. Glow sticks in floating gallon jugs marked our exact path and volunteers were standing by to help if needed.

Some riders advise pulling your feet up out of the water to avoid cold water cramps. Julie Suhr, undisputed queen of the Tevis trail, had advised me differently, saying that after 90 long, hot miles, nothing will feel better than that cool water on your feet. She was right, it felt fabulous. I knew I would mostly be staying in the saddle from here on in, except at our last remaining check point and the finish line, and I wasn’t worried about blisters from running in wet shoes.

On the far side of the river, the trail narrows for a mile or so and we came up behind a string of riders walking slowly with flashlights in all directions and glow sticks dangling everywhere, including off the tail of the last horse right in front of us (a rule has since been added not to do this). There was no way to pass, the swinging lights were making me nauseous, and I could tell John was impatient, repeatedly pulling at the bit and pinning his ears in annoyance. I politely called ahead that we would like to pass when the trail allowed, and heard a reply that they would pull over when they could.

A mile down the trail, now thoroughly tired of seeing the light show ahead (I was actually riding with my eyes shut by now to keep down the increasing nausea), I heard the call, “It’s wider here, would you like to pass?” YES, WE WOULD. With a thank you for their trail etiquette as we jogged past, we were in the clear and alone again. I have no aversion to riding with friends at times, but tonight, I only wanted to be with my horse, my ride and this amazing trail in the moonlight, listening to the river whispering to us. It’s part of the magic of Tevis, and not to be missed by indulging in idle chatter that can wait until the next day.

Once past the crowd, I dropped my hands onto John’s neck. From long experience, he knows that this is my signal to him that our speed is his choice. He could walk if that’s what he preferred, or anything else. I expected him to drop into his usual favorite working gait, an efficient stepping pace of around 8 - 10 mph, but he had other ideas. As soon as he felt the invitation, he stopped briefly to shake, stretched his neck forward and gleefully broke into a 12 mph hand gallop. Surprised, I bumped him back just a bit, thinking he had misunderstood my question, but he’d understood me perfectly well. He said it was time to go and knew we were headed for home.

I knew this was completely crazy, riding a horse at a gallop in the dark, on trail unfamiliar to me, after already having done 90 miles of the meanest trail on the planet in record heat. The moon was up but the trees overhead prevented me from seeing anything other than patches of light reflecting off the river to our right.

Then I thought, “Either you trust this good horse that has always taken care of you, or you don’t.”

I bumped John gently in the mouth once more, asking, “Are you sure this is what you want to do?” He cheerfully but firmly tugged again, relaxed and moving easily, not putting a foot wrong. As clear as day, he was telling me, “Mom. I got this. Just ride.”

So I did.

When asked what was the best part of their Tevis ride, many riders have replied it was receiving their award buckle, getting out of the saddle for the last time, or taking a shower afterwards to wash off the sweat and grime. For me, our best moment will always be galloping alone in the dark less than ten miles from the finish. I was unable to see anything but flashes of moonlight, cooled by the self-made breeze against my face, and feeling the smoothly flexing muscles of my horse beneath me, as familiar and necessary as rising wind to a hawk. In that moment, galloping with my brother, we weren’t just riding for a buckle or a photo. We were pagan forest demi-gods, if only for that brief moment in time. That memory will be enough to last me a lifetime. The buckle became the memento, not the goal.

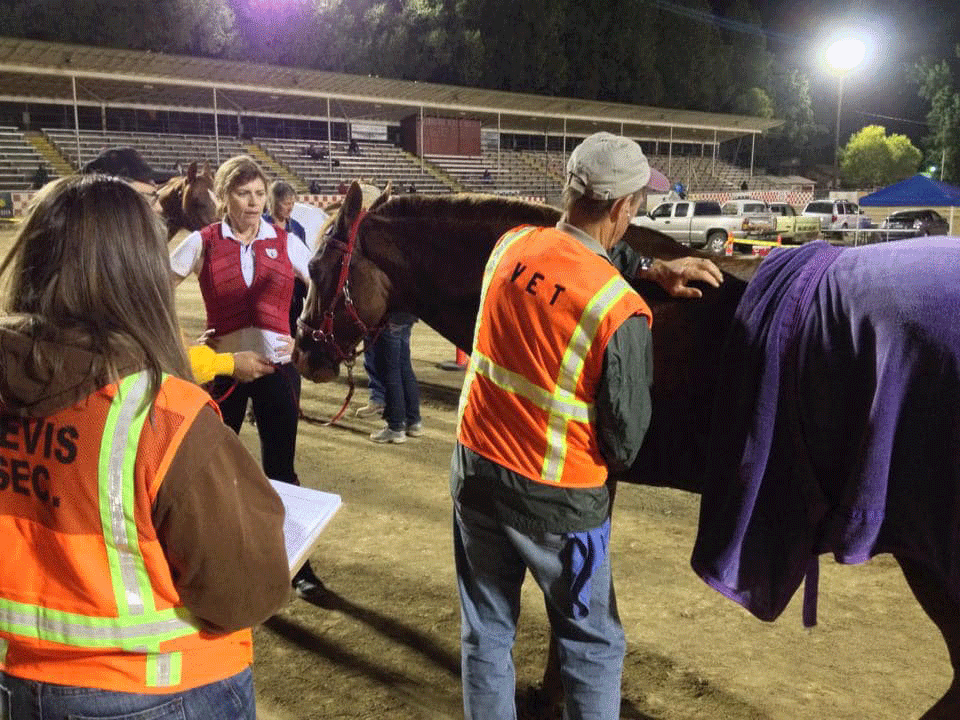

The lights of Lower Quarry at 94 miles, our last checkpoint before the finish, came into view and we jogged in, John smug and pleased with himself as ever. I worried that having galloped the last several miles would affect his ability to reach pulse criteria without taking a long time to relax and get thoroughly sponged down. He cruised in like he owned the place, took a deep drink and was at 56 bpms.

We vetted straight through and I let John slurp up sloppy mash while I wolfed a half-sandwich from the table. Processed turkey and American cheese on Wonderbread had never tasted so good. I grabbed another flake of dunked hay to hand down to John as we rode and we were off on the final six miles to the finish.

As we got closer to the Overlook, the trail narrowed to singletrack and John was content to just walk up the last 500’ climb behind a line of other dirty, tired horses and riders. After our long journey together, it was almost an anticlimax to see the finish line ahead of us and to give our number to the WSTF volunteers. I heard my husband call out to me, “Did you wait around on the trail so you could come in JUST then???” I didn’t know what he meant—he later explained that I had crossed the finish line within two minutes of our ride plan, something I never would have expected after all of our ups and downs of the day.

We finished at 3:12 a.m., with a ride time just shy of 20 hours, in 29th place. John was the only gaited horse to finish that day and one of only two horses to finish that did not have at least 50% Arabian heritage. The other non-Arab was a tough little Appy named Crow Pony, who finished at 4:32 a.m. with Robert Ribley picking up his 13th Tevis buckle.

We were five hours behind the winning horse and 2 1/2 hours out of Top Ten. It didn’t matter—-we hadn’t come for a placing. We were there hopefully for a completion buckle, for the adventure, and to see what this kind, humorous, shouldn’t-be-an-endurance-horse-but-let’s-do-it-anyway, endlessly tough horse could do. And what I could do with him—and also with myself, as well, after all the surgery setbacks, the pain, and the tears.

As we entered McCann Stadium for our ceremonial victory lap before going to the vets, I once again heard the now-familiar comment from onlookers, “THAT horse finished? What breed is he?” My friend Jonni Jewell, who was leading us down and this year herself going for another buckle of her own, turned with a smile and told them, “He’s a Tennessee Walker. That’s John Henry. He’s not just any Tevis horse.”

John picked up a jog and I remembered one last thing we had come to do. I reached down to my pommel bag and gave it one more tap. The last pinch of the ashes of my friend and fellow endurance rider Gesa Brinks sifted down onto the ground as we crossed under the banner. It was the best we could do to bring her the completion that she had so wanted.

John passed his final check and my crew shooed me away to go clean up, eat and nap while Julie and her minions took over taking care of John. After washing him, feeding and wrapping his legs, Julie curled up in a chair next to his stall for the next five hours to watch over him. While I get to wear the buckle, Julie and my crew had worked as hard and earned it every bit as much as John Henry and I had.

Later that afternoon, we arrived for the awards banquet, still tired but exhilarated and looking forward to the celebration. That was a year in which Legacy buckles were available—-buckles that had previously been earned by earlier riders, many of them multiple buckle winners, who had generously donated them back to be awarded again to a first-time finisher. I had signed up, but had no idea whose buckle I would be handed. As I crossed the stage and headed back towards my seat, I couldn’t wait any longer. I pulled out the buckle that, while newly polished, had the patina of a sterling silver buckle that had been well worn and well loved. I turned it over to read the inscription, ‘Julie Suhr - Marinera - 1966.’ It was finally all too much, and I burst into tears. Julie later told me she had picked out that particular buckle because her Peruvian mare Marinera had also been a gaited horse.

Some weeks later, I looked up the date that Julie had originally won that buckle that I now wore. It was her second of 22 buckles she eventually earned, and she did it on July 30, 1966.

Julie had no way of knowing, but that date was just three months after my mother, born the same year as Julie, had died of metastatic breast cancer. The same breast cancer that killed my mom also took Gesa Brink’s life and tried to take mine. Of the three of us, I was the only survivor. At the time of my mother’s death and Julie’s 1966 Tevis, I was six years old. I had no idea at all about what Tevis was, or about the buckle being worn by a tough, kind, consummate horsewoman who would give it to me, 47 years later. I was just a little kid that loved horses.

John Henry and I went again to the starting line at Robie the following two years, and finished both times. In 2015, I had terrible leg cramps for the last half of the ride that turned out to be a side effect from my ongoing cancer treatment. John had to work harder than I had planned to carry us through, but carry us through he did.

In 2016, I loaned him to a friend, Lisa Schneider, who rode him to her seventh buckle and John Henry’s fifth—-four of them in a row, and his fifth completion out of six starts. It tied him for the record for gaited horse completions, a record that has stood for over forty years. It also put his name onto the Wendell Robie Trophy for horses with five or more completions.

In 2019, John suffered a devastating and potentially life threatening (never mind career-ending) laceration to his fetlock that sliced through ligaments and into the joint capsule. We still don’t know how he did it, but he let me know he needed help by standing at the fence nearest the house and shouting until I came to investigate.

He went to UC Davis within a few hours of the injury for surgery that same day, and spent a month hospitalized under their diligent care, with no promises that he would ever be sound enough to ride again, let along compete. He eventually came home to again invoke the It Takes A Village rehab program for the next year with bandage changes, hand walking progressing to easy outings under saddle. Thirteen months after the injury he finished 50 miles happily pulling like a train at the Camp Far West ride. And once again we started musing——could he actually do Tevis one more time to beat the forty-plus year record for gaited horse Tevis completions? Every time he was asked, his attitude continued to be “let’s go”.

John went out to happily romp through the Cache Creek 50 in May with a good friend Brenna Sullivan, but a back injury prevented her from riding John at Tevis that year in 2021. John was now 21 years old, but was working well and we decided to put a last minute rider, Jenny Gomez up, even though she had never ridden John in competition previously, other than a few practice rides. I dreamed of riding those trails with my best friend one more time, but my own health status said otherwise, and I wanted to give John the best possible chance of finishing in good health.

Both Jenny and John Henry did their best, but were delayed when another horse ahead of them got in trouble on the narrow and steep switchbacks and blocked the trail for over an hour. One of the carved-in-stone rules of Tevis is no matter what, horses must cross the finish line by 5:15 a.m. John and Jenny made it to the Overlook, but 24 minutes overtime. They had done all 100 miles despite delays beyond their control, but it did not count as an official completion. The record stays untouched.

John is now turning 24 years old, although he remains convinced he is still a rowdy ten-year-old. After a tendon strain that proved pesky in resolving and took 18 months of slow and careful rehab, he is working happily and soundly and has finished two tough 50 mile rides this season with Dr. Melissa Ribley in the saddle. I was again casting about thinking of who to ask to ride this year when Melissa said she would like to ride him. It was like needing someone to sub for a high school garage band because Timmy the sorta guitarist got mono, and having Eddy Van Halen show up.

Win, lose or draw, Tevis 2024 will be John’s last 100. Will we continue to take him to a few fifties or LDs? Maybe, at least until he says he isn’t having fun anymore. I’ve learned not to predict what John Henry is going to want to do next, but he makes it very clear when he is not happy, and I know to listen to him. Maybe my own health will improve enough that John and I can toe the starting line at a ride just one more time or two together, and see if he tells me once again, “I got this, Mom. Just ride.” And just be forever grateful for this magnificent soul in my life.

Someday, I’ll have his name, and mine, engraved onto the back of that 1966 Legacy Tevis buckle next to Julie Suhr’s and Marinera’s. Someday there will be another gaited horse finishing their first Tevis, and we’ll pass along that buckle to them.

But not quite yet.

See you next week at Robie Park.