Tevis Cup 2007: Frantic and Precarious

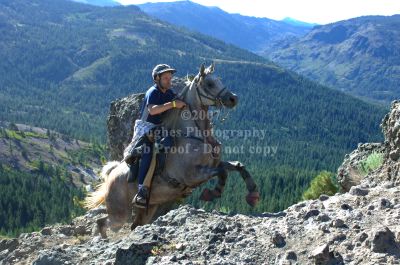

The above photos are copyrighted pending purchase from Hughes Photography (707-575-8301): Crossing Cougar Rock!

They say there is 19,000 feet of “up” and 22,000 feet of “down” on the Tevis trail across the 100-mile span from Truckee to the Fairgrounds in Auburn: the hardest and most coveted 100-mile race in the world. The stigma and safety issues have kept me away from Tevis and I always assumed that visually the ride would be as unforgiving as the technicality of the trail. I was very wrong: it is one of the most breathtaking locations on earth. The vistas are wide and the pines are strong; the rock formations are incredible and the lakes and rivers are the gold leaf on the crown of Tevis.

Our Tevis departure date came upon me very quickly. The activities at work in the weeks leading up to the race had actually diluted my opportunity to focus too much attention on preparation. There had been some shoeing issues, and after loosing three shoes at the educational ride in June, the chance of my actually starting Czar on ride day was beginning to seem less and less feasible.

I felt like I was on the list under false pretences: the subject of Tevis had only come up in February, when I offered to crew for Clydea at Tevis in 07 as a gesture of thanks for letting me ride Zeb at three 50-mile rides during the winter while my young horses were being legged up to compete later in the year. Clydea smiled and nodded on the few occasions I mentioned it, but it was not until we were at dinner together one evening when she said “Rather than crewing for me, I would actually prefer it if you would ride the Tevis with me.” Why would anyone refuse an offer like that? Clydea has ridden Tevis at least six times, and this would undoubtedly provide a very rich experience for me to paste into my book of memories.

And so the training and planning and riding and strategizing began, overtaking most other things in life, or at least becoming embedded in them. We trained consistently – and I learned much from Clydea about building distance and speed. We drove up to pre-ride the last 66 miles of the trail in June, which showed me just how risky this ride was to be.

Clydea and me signing up for Calstar Helicopter Airlift Insurance!

Robie Park, just outside Truckee, CA - Checking In

And suddenly it was time to leave for Truckee. We hitched, loaded, planned some more, and pulled into Robie Park on Thursday morning. Jim and Clydea found the perfect spot and our crews arrived on Friday, allowing us time to divide the crewing responsibilities between them and between the only two locations they would be able to attend. The vetting-in was uneventful; the crew bags and equipment was split into three trucks, and everyone dispersed to their strategic locations well before sunset.

I slept peacefully and woke at 3:15 AM on July 28 feeling rested and ready. We saddled in the murky darkness and mounted by 4:30 in order to get into the second pen for our 5:00 departure to the 5:15 AM start line. There were about 70 horses circling in our pen in the darkness. Most of the horses and their riders were composed; some were a little strung out. I thought how wild it must have been in previous years to have 250 horses and riders milling around waiting to start.

And so the ride began (contrary to the above photo, it was VERY dark and VERY dusty). We walked the 15 minutes along the park road to the start line – three and four horses deep. Most riders were polite; others pushed their way through to the front of the group, and others still managed the rearing or kicking antics that were justifiable in such cramped and charged conditions. We stopped a few times along the way – no doubt to prove the queue theory correct – and after what seemed like an hour, we were suddenly in the chute of starting horses trotting out and down a long hill. I thought the adrenaline rush would overwhelm me, but it felt good – really good!

We all trotted out at a good clip – perhaps as much as 10 mph down the twisting jeep road. Don’t believe a thing they tell you about the dust on the ride: it’s much, much dustier than you can imagine. It’s not Oreana dusty – it’s a powdery, talcum-powder-like dark brown dust that puffs up under foot as deep as I am tall.

There was lots of bumping and pushing and nerves; some riders flew past – one or two riders came off – and within a short while, we were down to the highway crossing. The crossing actually involves riding on the trail under the highway bridge, then coming up on the other side and riding along the side of the bridge on the road behind a concrete barrier to a single-track dirt trail up and off to the left. It was uneventful for me, and the change from a downgrade to a climb was welcome. We continued to move in one long cross-country train and I was blessed with a rider behind me who insisted on giving a running commentary to the riders behind her as we changed gates and speeds depending on the terrain and the effects of the queue theory. The horses were delighted to oblige us in moving along at quite a clip, and we began to pass riders who moved off to the side to let some of the train move ahead of them. The horses banged and stumbled their way along the trail that constantly challenged their balance and ability to sure-footedly dance across the rocks. The dust simply hid the trail and the traps along it.

We wove our way down to the ski-hill road and began the long climb up to the peak. The dirt road was good and hard-packed, and this was the first time we alternated walking with trotting as the elevation increased and the air got thinner. As we neared the top, Czar felt a little off on the front left. I asked Clydea to watch him as I trotted and I could tell from her face that she could see it. My heart sank. It was the foot that had lost several shoes, and there was so little hoof to work with that we knew the risk was high. I was distressed by the thought of getting pulled at six miles at Tevis. Clydea encouraged me to continue on: “You are not out of the race yet!”, she said. She was right.

We let the horses eat and drink for a few minutes at the summit, then wove our way into the Granite Chief Wilderness area. There were photographers and film crews littered along the trail – just how did they make it out so far? Suddenly we were all spread out – no more bumping and pushing. We wound our way along the side of the wilderness; trotting along the good sections and walking across the rocks. It was as if a switch has been turned and we were suddenly in control of our own ride. We went through the infamous bogs, which were apparently much drier this year. We moved along at a fair rate, but it was not rushed, and as the odd rider came upon us, they would pass without much discussion. It felt good to get into a groove – to put the horses into fifth gear and get down to work.

The trail spilled out onto a tree-lined jeep road after some miles and suddenly we were upon Lyon Ridge. A sophisticated trot-out system was being successfully employed, and there was a refreshment tent with melon and Gatorade and water for riders. There were stations of rich, leafy alfalfa and freshly made bran mash laid out up the hill for the horses. Some riders were standing off to the side, having been pulled at the trot-out. Czar looked sound and so I asked no questions and moved through to refill water bottles and let the horse begin the first of his frequent and brief grazing (with bit in!).

After only a few minutes we were off again – the trail wound its way up and the views of the lake off to the left were absolutely stunning. We climbed some more, and as we turned a corner, the much-debated and revered Cougar Rock appeared. I was caught off guard – I had still not made a decision about whether or not to climb the rock or take the safer detour. I had also not expected to see a small army of people right there, and, I suspect, nor had the horse. Facing a potential lameness pull, and drawn by the prospect of the eternal Cougar Rock photo on a shelf somewhere for the rest of my life, I gave Czar a little leg and we moved forward. A traffic policeman approved our desire to climb the rock, and as we took the first couple of steps up, we were suddenly aware of four or five people standing almost on top of us on the rock above us, and of horses down to the right of us, taking the detour. As I took in all of the commotion around me, a reassuring voice said “That’s right; you’re doing a great job; follow the arrows on the rock – that’s right – off to the right – you are doing really well!”. It was not the little voices in my head talking – there really was a lady up there above me talking me through each step. It was obscure but it kept my focus on the job at hand and I felt rewarded for doing the right thing with every step. And whoosh – we were over it. It seemed slippery and challenging, but not necessarily harder than any other ten-step rock climb on a horse!

Click on the arrow above for a video of some horses crossing Cougar Rock. Czar appears at 2:40 and Zeb is behind him. The video gets more entertaining if you watch until the end. Check out both hind shoes coming off the horse just before me!

Clydea was behind me within moments, and we set off along a rocky, twisty trail through the pines that allowed us to walk and trot and make good time. The trail sent us out onto a hard-packed dirt road that felt unforgiving under foot as it rose and dropped and turned and rose and dropped and turned. It would be an eternity until we arrived at Robinson Flat.

As we turned the 100th corner, some eager crews were in sight. We jumped off the horses and loosened the girths. People clapped and cheered as we walked in – something I am not used to at 36 miles into a 100! It was 10:46. I scanned for Rusty, and before we knew it, the horses had been unsaddled, the crew were walking them to the in-timers; the interference boots were being removed and the horses were again treated to leafy green alfalfa while they stood at the water and were sponged down. It felt odd to relinquish control of the equine, but we got into line, got the pulses down and vetted through before heading up the climb to the spot where we would spend the next hour. There were lots of people there: Jim, Dee, Dee's friend, Robbi, Rusty, Jan and her brother, and lots of hands helping and thrusting things at horse and rider – Starbucks Double-Shots coffee; energy drinks; cashews, fresh fruit, granola bars. It was all very confusing as I sat in the chair and watched Czar chow down. Someone washed the brushing boots, someone prepared electrolytes and on and on. It was quite frantic.

The hour hold was soon over and we had to get an exit CRI before we left, so we tacked the horse back up by committee and moved back down the hill to stand in line for the vets. Czar went through fine, but Zeb needed to go back to the vetting area to be checked again by the vet. This was not good – it meant they saw something questionable in his gait. I wringed (wrung? wringed?) my hands and Czar began to panic as his stable buddy was led to the vets for a re-check. Leslie was there to help and her Mom acted as messenger. Wait! No, go! No, wait! I got a crop ready, since I knew Czar could get a little light in the front end when asked to leave Zeb. Zeb had the green light to go and we set off into the wilderness that would take us down 2,500’ in less than ten miles. This was the part of the trail we had ridden in June and it felt very different to set out on trail that horse and rider had already seen. Clydea was quiet as we wound our way down the mountain, through dustier trail and across rocky and rooty sections of the trail. We moved along at a fair clip and the heat and the dust began to take their toll. I felt overheated and tired already.

I opted to take a few minutes at Dusty Corners to put two Easyboots on Czar’s front feet. He still felt OK, but I was worried about the 60 miles or so ahead of us and I wanted to reduce the risk as much as possible. I struggled a little to get the boots on, but as we trotted off down the road and took the trailhead that would take us to Last Chance, Czar felt much more sound at the trot. I was pleased and felt mildly confident that we stood a chance of getting through this. By the time we pulled into Last Chance at 50 miles, it was hot and the horses were dripping in sweat. We lingered for a while at the alfalfa station; the horses were beginning to look a little fatigued. It was 2:02 and the volunteers were thrusting bottles of cold water and sliced watermelon at us. It was as if we had arrived at an oasis. The infamous trio of canyons lay just ahead of us and they had been the cause of much anxiety for me at the pre-ride. I felt prepared and focused enough to take them on and we moved on to the vets for them to inspect the horses. I got to a vet before Clydea. His pulse and metabolic indexes were all within the norms, but I was asked to trot him out a second time. I was sure it was the left front the vets were seeing, but they liked what they saw the second time and I was cleared to go. As I looked up, Clydea was on her second trot-out. No, Zeb was lame and she was suddenly pulled. What!? I was being asked to move on so the stream of riders behind me could vet through and leave to take on the dreaded canyons.

I got a stick and mounted up and encouraged Czar sternly with my voice to abandon Zeb. This was all wrong – it was me who should be pulled and Clydea who would go on to finish. I was stunned.

So off we went, my attention was soon to be absorbed by the challenges that lay with every step of the precipice trail. I quickly settled in behind Fifi d’Or and Rooster the Stallion, who were attacking the trail with great gusto and confidence. I hung back enough so as not to crowd, but let them determine my pace. Rooster’s rider was off and running down the steep switchback grades. I had experimented running down that trail in June when Nancy Gabri was kind enough to take us out on the trail. I had regretted it physically quite quickly, and I decided I would stay mounted and get off when the long climbs began. The trail was less overwhelming that it had been in June – the goal of getting into Auburn on horseback sometime the next day was inspiration enough to remain calm, focused and centered.

Wow. We were at the swinging bridge. As if not to scrimp on the experience, the bridge really was swinging by the time I made it 1/3 of the way across. Rooster’s rider had decided to make a running mount back into the saddle halfway across the bridge. So he took a few steps at a run, jumped up with both feet and promptly missed the saddle, jumping back down onto the bridge with both feet. I felt the whole bridge weave and warp and I stuck my legs and arms out like a stuffed pig in order to steady myself (not that there was anything with which to do so). Czar did the same thing and as I looked up to plan my evacuation, I saw a volunteer at the other end of the bridge with eyes as wide as dinner plates. I continued to move forward, and we were across and beginning the hardest ascent of the ride up to Deadwood.

I stayed on for a while, but the stallion in front of me was causing a little drama and was eager to catch up with the mare in front of him. Without any warning, Rooster was galloping up the hill and Czar responded by doing a full body tremble from the shoulder to the hip. I was worried he would tie up, so I hopped off and led him up to Devil’s Thumb by hand - about 1,500 feet of elevation gain in less than three miles.

Czar at Devil's Thumb. I was more tired than he, I think

I was overheated and physically spent by the time I got to the top, and Czar looked like he felt the same way. We hung out at the water for a while, and then I struggled to electrolyte him, much to the horror of the volunteers who thought I needed help to control the horse that would not take the syringe. They were making it worse: the thing Czar hates most is a stranger trying to hold onto his head while I stick a syringe of salt in his mouth. Poor guy! After five minutes of sponging down and recovering, I walked him the remaining mile into Deadwood. We both enjoyed the refreshments and the bees there for a few minutes. The bees, I was assured, would not sting, so we made it over to the vets and he vetted through just fine. The vet told me that whatever he had seen at last Chance had not become any worse, in spite of the challenges of the canyon, and that I was good to go on. I stayed for at least ten more minutes – Czar was famished and I could not bring myself to drag him away from the rich and plentiful alfalfa. When I did finally get on, Czar’s stubborn streak revealed itself (a sign of a horse with heart and determination in my opinion) – he got a little light in the front end and refused to go out. As I pointed him towards the trail, he would rise slightly, turn on his back feet and head back for the alfalfa. I think the people at the vet check were horrified! I tried the stern, angry voice and a stick, but to no avail. So I employed the reversing out of camp tactic. I made a big joke of it to the entire vet check who were now fully focused on what would happen with Czar and Kevin and pulled an Eddie Izzard in my best English accent: “Goodbye – thank you very much”, I said as I waved a big full-arm wave while we backed out of camp, “goodbyyyyyyyyeeeee – thank youuuuuuuuuu!”

We turned the right way within 75 yards and headed out onto the trail that would take us down more than 2,600 feet to El Dorado Creek in less than two miles. I hand-walked him for the last mile or so down, and as we started to head back up the 1,800 foot climb to Michigan Bluff, Czar got really pluggy. The heat and humidity of the day were now at their height, and I could tell by the way Czar was moving that his muscles were getting tired and weaker. We made our way up the hill at the speed of molasses on a cold winter morning in Missouri. It felt like we would never reach Michigan Bluff. I was tired and so was the horse, and it had been more than 1.5 hours since we had left Deadwood. As we inched our way into Michigan Bluff at 62 miles, I was pleased to see Rusty and Robbi and Dee. They gave Czar some wet oats and water, and they gave me one of DeWayne’s energy drinks that really helped. Robbi consoled my worries about Czar’s energy level and encouraged me to just let him be and not to push him too much up to Foresthill: that his energy level would soar again once the sun went down. So I got back on and continued the climb up to Chicken Hawk where we would vet through without any issues before taking on the last and lesser canyon that would take us down to Volcano Creek before climbing back up into the milestone vet check of Foresthill.

I got to Bath Road just before Foresthill at 68 miles by about 7:20 PM. Jim took the horse and the saddle was off before I knew it; the horse was being sponged down and the roadside was littered with people clapping and cheering. It was a real lifter of spirits to feel the encouragement, but I knew the ride was far from over, and that the worst of the trail was yet to come. The horse vetted through looking really good at 7:35 PM, and we went back to the trailer where I took a shower and changed all my clothes before sitting down.

Waiting in line at the Foresthill Vet Check

Click on the arrow above to see Czar getting cooled down in preparation for vetting through; then his trot-out (thanks Rusty!), then our departure into the night.

As I relaxed, I began to feel the effect of the day and began to feel dizzy and weak. Lucy and Jan were there helping out; Clydea was fully in control of managing the horse, and Rusty was the rock. I chugged two big bottles of Gatorade and munched on some fruit and some cashews. I really felt pretty sick – not something that usually happens to me on a 100. When it came time to leave at 8:35 PM, I got on the horse with some trepidation. I had really not enjoyed the psychological stress of riding the California Loop and its steep drop-offs when we rode there in June, and I was wondering how it would feel to remove the element of sight!

I was able to hook up with another rider as we set off down the blacktop road through the center of Foresthill. People were still out on their chairs clapping and encouraging us out into the soupy blackness of the night. The balcony at the local bar was full of people cheering, and the main road through town was full of big trucks and trailers pulling out of the vet check to make the drive down the mountain to the fairgrounds at Auburn. It was frantic out there and I felt overwhelmed and under resourced! We turned left at California Street, bearing away from the distractions of the town and then down onto the switchbacks that would take us down 2,400 feet over the next ten miles.

I knew there were a couple of water crossings over little streams in the first part of the trail. When we were there in June, Czar had jumped one of the streams, landed very poorly with his front legs on a slippery rock, and almost gone over. I was concerned that he would do the same thing again, so I dismounted fairly quickly and hand-walked him to where I thought the challenging crossing would be. Well, I got off far too soon, and probably hand-walked him about a mile, which was a silly thing to do strategically. I was riding with Jackie Hathhorn from Minnesota, who was very patient and forgiving. Czar crossed the stream without blinking, and we set off at a trot into the mysterious night.

As the emotional fatigue increased, so too did the variance in speed and gait. We would trot for a while, then walk for a while without really knowing what we were riding over or through. I discovered that the unknown was less foreboding if I was leading on horseback rather than following. And in some ways, the revered California Loop seemed to invoke less fear at night than during the day when you can see how steep and how far the drop-offs are. One is also much less aware of the width of trail at night: during the day I had the sense that I was riding along the top of a wall, whereas the night riding gave me little sense of that.

The loop took longer than I had hoped: it was past 12:30 AM when we pulled into Francisco’s at 85 miles – more than four hours after leaving Foresthill to ride the 17 miles. I had been told not to linger at Francisco’s, but I still managed to clock about 23 minutes there. The vetting went without a problem – it was not as cold as I had expected and the revealing white floodlights over the grassy field felt welcoming and the company was good. The volunteers at Francisco’s were upbeat and jovial; there was a hospitality table full of food and drinks that would probably have looked more interesting if I had not spent the last four hours fighting nausea. After three trips to the bathroom and two failed attempts at eating the pb & j sandwich, Jackie and I set back off into the night, using the vet check to leapfrog a group of 30 riders. We felt the psychological push of wanting to avoid a 30-rider freight train come up behind us on the trail. Jackie led; I felt much better physically, and the trail descended to Poverty Bar as we moved along at a good working trot. Life was good!

We approached the pebbles and rocks on the bank of the American River in no time; passed the Mexican beachfront beer stand complete with jalapeno lights and followed the glow sticks that lay under the water like an airport landing strip. It looked like a no-brainer. I quietly gasped when the water came up to my shins – on the horse – it was much deeper and colder than it had been when we crossed in June, and it took me by surprise. I had a fleeting moment of worry about the horse cramping up from the cold, and then was distracted by the rushing current that forced my feet deeper into the stirrups. I consciously pulled them out of the stirrups to the point where just my toes were still in; Czar stumbled a couple of times and then we climbed out on the other side. We climbed up onto the single track that would take us onto the road leading to lower quarry. Jackie was still leading, and as we trotted off I felt that dreaded sensation of a horse who lands heavily on one foot. “Jackie, I think he’s slightly off!” I glanced down to see if his easyboots were still on and saw enough to tell me that they were still there. I really wanted Jackie to wait and maybe even to hold my horse while I inspected all four legs, but it was dark; the clock was ticking and we could sense the presence of other riders coming upon us and Jackie was eager to move on. So I let her go and elected to walk the next five miles into Lower Quarry.

I lost quite a bit of time doing that, and got passed by at least 20 riders. I was surprised at how much calculating of miles, time and distance was going on. Some riders would stop and walk with me for a while, probably glad for a little company or for the break in pace. Everyone agreed that time was still (just) on our side, and that we could more or less still coast into Auburn, still make it before the 5:15 AM cut-off and significantly reduce the risk of a lame horse by slowing down the speed. Deep down, though, I was sinking: I knew Czar was off and I was coming to terms with the devastating possibility of being pulled at 95 miles. It was the lowest point of the ride for me, and the slowest. It took me 1h25 to walk the five miles to the vet check, and I went very begrudgingly to the vet. He asked me to trot out a second time and called a second vet to watch us trot. “Go further this time”, he asked, and my heart sank further. I trotted him out with as much gusto as I could muster and got quite a bit of speed up. I pride myself in having a good eye for spotting a lame horse, and although I could see something from the corner of my eye, it was not as bad as it had been earlier. As I approached the vets, I was aware of them nodding to each other, and then the magic words: “You’re good to go – there is something there but, it’s inconsistent. There is something going on with his right front, but you are good to go”. “Right front”, I thought “but it was his left front earlier in the ride!” With that, I glanced down and saw that the black vet wrap that was still wrapped around his foot had fooled me: I had mistaken it for an Easyboot. I wanted to hug the vet: I had completely missed the fact that he had pulled a boot when we crossed the American River. I got my last Easyboot out of my cantle pack and put it on. I let Czar chow down for another five minutes or so, and then with renewed vigor, we set off down the road towards Highway 49. Within moments I had caught dear Jackie and we set off at a working trot.

We crossed the highway and climbed up to the precipice trail high above the side of the road. Jackie was now very much in charge: she had ridden this trail at least six times and knew exactly where to trot, where to walk and where the good and bad footing was. It was like driving with a GPS! We weaved our way along the trail and then climbed down to No Hands Bridge. I had a fleeting moment of fear as we started across the bridge, but was soon distracted: Jackie was calculating time and distance and was predicting we would be at the Fairgrounds by 5 AM – a full 15 minutes before cut-off.

No Hands Bridge by Daylight

The last four miles felt like ten miles. I had underestimated how it would feel to know there were other riders on the trail behind me who would also be pushing to make it to the finish line before cut-off. I wanted to slow down and coast in, but the voices behind us seemed to get closer, and one rider was wearing a helmet with an aerial and a big blinking red light on the end. I was concerned that Czar would have a negative reaction if she got close, and the trail has drop-offs and sharp corners all the way until the end. There is no forgiving trail whatsoever! So we kept on: I would ask Jackie every two minutes or so if we would really make it before cut-off. 24 hours in the saddle was beginning to cause me to doubt her calculations and the finish line seemed to be getting further and further away.

After a few token trail challenges, we were finally up to the look-out point. I felt nervous for the final vet inspection to be over. Rusty and Jim and Clydea were all there and so was Robbi, but I was dazed and confused: it was 5 AM and I wanted to know that the Tevis buckle would be mine. We watered the horse at the top, then walked him along the blacktop, back through the barns, down the hill and across the slippery grass to the track at the fairgrounds. I was a hindrance to the process: too concerned about Czar slipping on the blacktop; concerned about the blanket falling off his back and making him fall over; concerned about having him trot out before he stiffened up and showed lame. I have been pulled once before at the finish line of a 100 and I intend never to do that again. I was lucky they didn’t all punch my lights out!

Czar trotted out sound – a little lackluster perhaps – but he was finished and we had completed. I was overwhelmed and in disbelief that I had really been part of the preceding 24 hours. Czar was walked to his stall; his legs wrapped and three or four weeks of food was placed before him.

Jim and Clydea headed off to their motel and Rusty and I headed to the trailer, where we would lie awake being annoyed by flies and sweat as the heat of the sun increased the temperature in the trailer. Note to file: always have a motel room for the morning after the night before!

After a few hours of not sleeping, we made our way to the fairgrounds for a welcome breakfast, then watched the presentations for Best Condition. After blowing my brains out at the Tevis store on merchandise I would not buy until I had completed the race, the awards banquet began, and I got my first Tevis buckle.

Thank you, Clydea, for making it all happen. You have given me the gift of pride and accomplishment. And Czar? What a horse! Is he a horse!

The moral of the story...

PS: If you have time and patience, check out http://www.foothill.net/tevis/ for data analysis and history of the ride.

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home